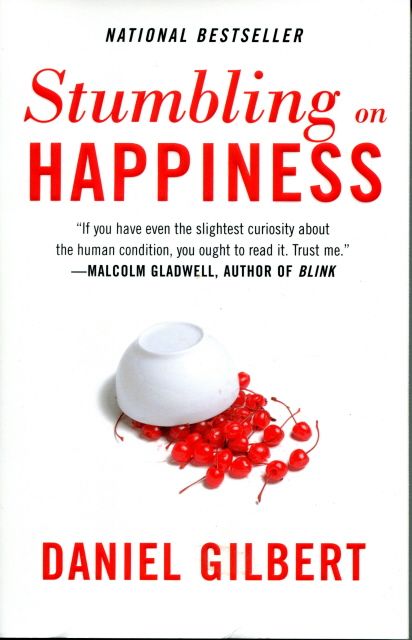

Why do we make choices and decisions about our future that makes us unhappy?

Stumbling on Happiness (2007) by Daniel Gilbert shows the complex manner in which our brain processes information and influences our decision-making process. Through everyday examples, the author explains how we can understand ourselves better and make decisions for happier outcomes.

The Brain Can Visualize What We Didn’t Saw

Our brain is wired in a way that it can fill in the missing details that lie beyond what we actually saw. It has the capability of creating the missing picture and construct a complete story through imagination.

It works in similar ways when it needs to remember past events. The information stored in our memory is so vast, that it only remembers key events. Therefore, our ability to recall the past is always a mix of imagination and reality and not the reality that we have experienced.

Example: If we try to recall a memory of a bad experience in a restaurant, the brain will bring forth only key details like an argument with the restaurant manager, the manager apologizing, etc. It will fabricate the rest of the event, like the general set-up of the table, the manager’s facial expressions, etc.

The brain does this so fast, that we are often unaware that the brain has made up these details.

Our Brain Predicts Futures

The brain perceives the immediate future on the basis of past experiences and general knowledge. Once the future is predicted, we cannot see any other alternative to that future. Moreover, we set our mind to believe and trust that it is a good prediction, without considering any other outcome.

Example: If we are going to visit a friend’s house we have never been to, the brain will fabricate a picture of us enjoying the evening with the set of friends. It will then create images and fill in details of a glass of wine, laughter, etc. But it will not consider a possibility of heavy rain canceling the visit, or say, a flat tire on the way.

This happens because we tend to trust the brain’s visuals of a good evening and leave out the negative outcomes. Our brain has the habit of making positive predictions for all our futures, making us blind to any other possibility. We trust our predictions of the future when they are merely a single scenario among many.

“If you are like most people, then like most people, you don’t know you’re like most people.” — Daniel Gilbert

Mistakes Happen Because of Emotions

We tend to believe that our predictions of the future are rational. What we do not realize is that these predictions are largely influenced by our emotional states at that time.

The brain has evolved over time to focus on the present (for survival) rather than the future, and our present emotional states influence even our future predictions. Therefore, the future predictions of the brain are rarely reliable.

Example: If a person wants to create a presentation for work in an angry mood, the brain will be unable to conjure a good outcome. The person will tend to focus on other negative factors such as getting anxious while presenting, mixing up important numbers, etc., and the pessimism may even lead to the person postponing or canceling the work.

Due to this influence of our emotional states, we tend to make mistakes while making decisions about the future.

The Brain Places Undue Importance On Price Rather Than Satisfaction

When it comes to the value of anything, our brain is wired to focus on the value of its price rather than the value of the satisfaction gained. This tendency is true for all commodities and products. However, it is a narrow view that can lead to errors in judgment.

Example: If we are buying a cup of coffee that costs a dollar more than it used to, we think it is overpriced. We place more value on the increase in price rather than the satisfaction we gain from it. If we compare all the things (like a parking space for five minutes or a pack of gum), that we can get for the same price of coffee of $2.5, we would perceive its value it differently. The brain uses the yardstick of the past value of any product to decide whether it is overpriced or not.

This applies to many other purchases too. Due to this natural tendency, we make simple errors when money is concerned.

“Most of us appear to believe that we are more athletic, intelligent, organized, ethical, logical, interesting, open-minded, and healthy-not to mention more attractive than the average person.” — Daniel Gilbert

Unique Experiences Become Stronger Memories

The brain is conditioned to memorize unique and strange experiences over the regular and mundane ones. The brain tends to filter out regular happenings in our lives and remembers unique experiences with detail.

The brain has evolved to believe that these memories, which we can recall with ease, happen often. The brain makes inferences based on the better, unusual experiences, rather than the whole experience – which might not have been as great as our mind makes us believe.

Example: If we spend a week camping in uncomfortable conditions, and towards the end of the trip, we find a $100 bill, the mind will focus on the uniqueness of finding the money rather than the total unpleasant camping experience.

Therefore, we cannot only trust our memory while making crucial decisions, especially while deciding if we should do the same thing again.

We Believe Something More If It Benefits Us

The brain has a tendency to believe information if it is beneficial for us or the society, even if it is untrue.

Example: Everyone believes that if they have more money, they will be happier. However, this belief is relatively inaccurate. While having more money does make people happy (if they are raising themselves out of poverty), but looking at the larger picture, money does not bring infinite happiness.

Yet, people believe (and have been believing) in the false myth that more money equals happiness, simply because it is beneficial for not only an individual but for society and the economy as a whole.

We Often Refrain From Taking Advice From Others

Our brains are wired to think that we are truly unique individuals. It tends to make us believe that our experiences are unique to us. Therefore, the brain does not think that advice from others will be useful.

In reality, people have similar experiences and also react to these experiences in a similar manner. Therefore, it is quite possible that solutions can be sought by listening to other people’s experiences and opinions.

Example: A person planning to quit their job and go on a world tour will tend to keep thinking about the pros and cons of their possible decision. However, if a friend offers advice about traveling, the person will tend to disregard the advice thinking that their situation is different, and the advice irrelevant.

This tendency can be detrimental to making good decisions.

“Among life’s cruellest truths is this one: wonderful things are especially wonderful the first time they happen, but their wonderfulness wanes with repetition.” — Daniel Gilbert

The Brain Regrets Inaction

The human brain is designed to learn from bad decisions. It has a defense mechanism to look for positive learnings from unpleasant experiences in hindsight. Additionally, the mind is also wired to regret inaction. This is because, the mind cannot comprehend, and therefore come up with a valid explanation to events that it does not have information for.

Example: A person will regret not marrying a noble prize winner whereas, will consider marriage to a murderer as a bad decision. The person will, in hindsight, think that they learned something from the bad decision of marrying the murderer, whereas, because he cannot draw conclusions from past experience of marrying a noble prize winner, will regret the decision.

We often do not know that our brain works in this manner. Therefore, it is better to decide and learn from the mistakes rather than not make the decision at all, and to be stuck in inaction.

We Have A Built-In Defence Mechanism Against Trauma

The brain sets in action a peculiar defense mechanism in the event of devastatingly traumatic experiences. It psychologically numbs us from pain to a certain extent, so that we do not get mentally crushed with the grief. This mechanism, however, does not engage for trivial experiences. It is due to this trait of the brain that we cannot imagine how we will react to extremely traumatic events.

Example: A person who has just gone through a divorce would start accepting the situation and bounce back faster than expected. At the same time, the same person will fret for days if they lost a phone.

We are often unaware of this defence mechanism and can make behaviours and decisions that seem strange.

The Paradox of Choice

The phrase, ‘being spoilt for choice…’ holds true for our brain. The moment the brain knows that there are alternatives, it is conditioned to explore those alternatives further. On the other hand, not having a choice at all makes our thoughts and decisions unidirectional, forcing the brain to see them in a positive light.

Example: If we receive a T-shirt as a gift from a friend and know that we have the option of exchanging it, we tend to start looking for reasons to exchange it. However, if there is no choice at all, we will not even think of why we don’t like it. The focus will be on the positive aspects of the gift.

We do not know that the brain reacts in this manner. Therefore, a lack of choice makes us happier rather than having multiple choices at hand.

“The bottom line is this: the brain and the eye may have a contractual relationship in which the brain has agreed to believe what the eye sees, but in return the eye has agreed to look for what the brain wants.” ― Daniel M. Gilbert

The Mystery In The Unexplained Appeals To Our Brain

There is a special appeal in the unexplained. Not knowing the cause behind anything, compels the brain to try and solve the mystery. The brain gets attracted to these rare, unexplained events eliciting a stronger emotional reaction.

When we get an explanation for the mystery, the brain loses the appeal. If the mystery is a negative one, then the explanation becomes beneficial, as the brain stops pondering over it and its impact lessens, however, if positive, then the excitement diminishes, robbing us of the happiness of that experience.

Example: If we receive a mysterious gift from an admirer, we tend to find excitement and happiness in the mystery of it. However, once we know who the admirer is, the excitement dies out.

We All Live In Our Own Echo Chambers

Our minds are conditioned to selective perception and retention. It has a tendency to only retain information which we already believe, ignoring the rest. This is evident in a person’s choice of friends. We tend to make friends with people who are similar to us.

Keeping this in mind, seeking advice and opinions from our friends could be biased due to the fact that it will most likely be similar to our own views. Without knowing this trait, we tend to put our faith in these opinions.

Example: One often finds that they share similar tastes in music with their friends. Therefore if they seek validation of their taste in music, it will be more likely that their friends will give advice that is biased due to these similarities.

The decisions we make about our future often cause us unhappiness because we are not fully aware of these unconscious processes that the brain is conditioned to follow. Unknowingly, we are susceptible to make errors in decisions leaving us unhappy with the results.

We need to pay attention to our cognitive biases in order to understand the way the brain functions. In ‘Stumbling on Happiness’ Professor and author Daniel Gilbert combines psychology, neuroscience, economics and philosophy to show how our imagination is really bad at telling us how we will think when the future finally comes. This book will help you eliminate a lot of noise with some powerful insights drawn from psychological studies.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks